Our story

Last year, in Design Computing Studio 2 at The University of Queensland, we put 140 students onto a project to develop a networked games arcade (a little like Steam). We gave the students a very small amount of code to start with, and over the course of semester the class made 4,883 commits and wrote 67,900 lines of code.

The students worked "supercollaboratively". They were in small collaborative teams of four or five students, but with thirty groups collaborating on a single project, building different features for the system. The project work was supported by GitHub, continuous integration, and static analysis tools giving regular build metrics. These are all regular features of real world projects, but this level of collaboration is not commonly how undergraduate students have been taught.

As this was a teaching course, of course we also supported the project with studio sessions and interactive teaching in class.

And it worked. Our students wrote games, networked multiplayer, event recording and logging, common UI overlays, achievement systems, and many more features. When our students graduate and interview for professional roles, if the interviewer asks about a project they've worked on, they will have quite a tale to tell.

This wasn't the first time we've taught this course.

A few years ago, we were dissatisfied with how undergraduates around the world are taught software engineering. Although some universities taught practices like version control and continuous integration, students worked on projects that were so small they could essentially do all their coordination and collaboration just by chatting to each other. The students weren't encountering the challenges of professional software development, so how could we expect them to understand the techniques we use to address them?

It is when someone you don't chat to every day starts modifying your code and pushing the changes to you that you discover the value of good tests and version control. It is when people outside your small group consume your code that you discover the value of good API design. It is when you are working on a busy project with a fast-moving codebase that you discover what "merge hell" is and how to avoid it.

So in 2011, the University of Queensland bravely let us redesign their software studio course to put all the students (nineteen groups of four) onto the same codebase. That year, we gave them a large legacy codebase to start from: Robocode. And we gave the groups different features to develop that we knew would need to interact with each other. This would be a project where students would need to put what we were teaching into practice in order to succeed. With seventy students on a project, you can't just get away with chatting to each other. And by and large, the students did succeed.

But, we had also asked the students to research and present half of the teaching content, which they didn't like, and our story for how we were going to mark their work wasn't as clear as it could have been. The course worked in principle, but there was work to be done.

In 2012, we ran the course again. We solved the marking problem and replaced the student presentations with interactive sessions where we'd introduce students to the different tools and techniques they would need. And this time we let the groups themselves come up with the features they were going to implement.

The course became even more cooperative, as groups had to talk to each other right from the beginning to come up with a feature that could interact with other groups, but would not be completely dependent on another team's success. Again, the students succeeded, but this time with fewer bumps and bruises along the way.

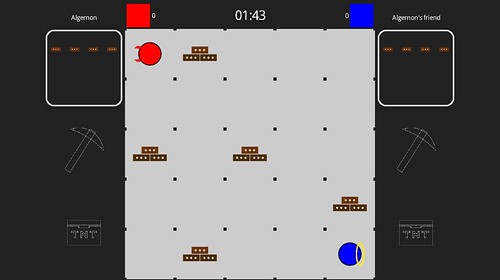

In 2013, our class size doubled. The course changed from "Software Studio" to "Design Computing Studio 2", a compulsory course not just for software engineers but also for multimedia design and information systems students. So, our cohort became larger and more varied. And this year we ditched the legacy codebase. Instead, we gave them a small amount of code to start from, a project structure, the build infrastructure, and a mission. We're building a networked games arcade using libgdx. Let's get started.

Again cooperation within the class improved, as they had much greater control over the architecture of the system as well as its features.

So now, we're keen to take this course out to the world.

On campus, the participants are all undergraduate students.

Online, cohorts are much more varied, and we hope there can be more peer-to-peer learning and mentoring within the groups.

On campus, we have to choose a single project, language, and build system for our 140-odd students.

Online, with your help, we can run projects in different languages simultaneously, so it does not need to be

one-size-fits-all.

On campus, we have the usual constraints of a course supported by a couple of teachers and a few tutors, and the

systems that we can write or maintain.

Online, students have resources of the world at their disposal, and the computing

community can come together to support and grow the course.

We think that doing this will bring students closer to professional practice.

If you are a tech company wondering where you're going to find the next generation of skilled and skillful programmers, then surely working with them in their project course is going to help you ensure they know the skills you need, and help you discover a few you'd really like to hire. If you're an engineer looking to step up and lead or mentor a team, then what better way to start than by helping students to learn their trade?

Whether you are a teacher, an engineer, a designer, a marketer, or whether you just want to take part, we think there is a way that you can contribute, and benefit, from this endeavour.

So, in the interests of building engagement, allow me to close by asking you this:

Are you supercollaborative? With your help, we are.